HISTORY OF DARK GROUND ILLUMINATION USING THE MICROSCOPE

As the resolving power of microscopes improved in

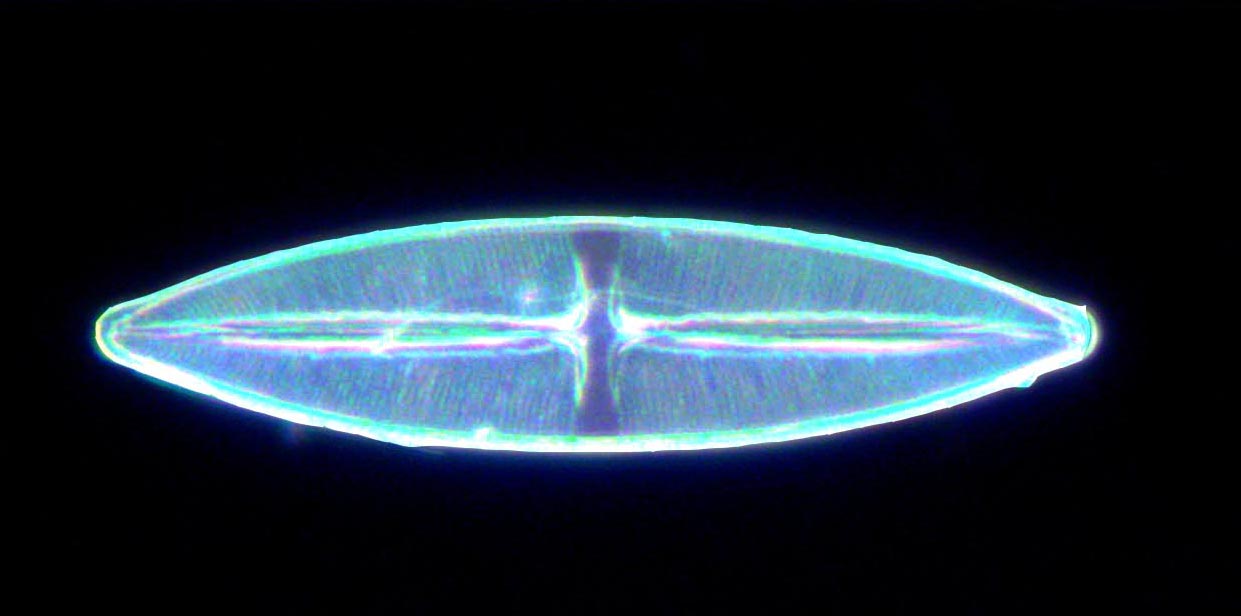

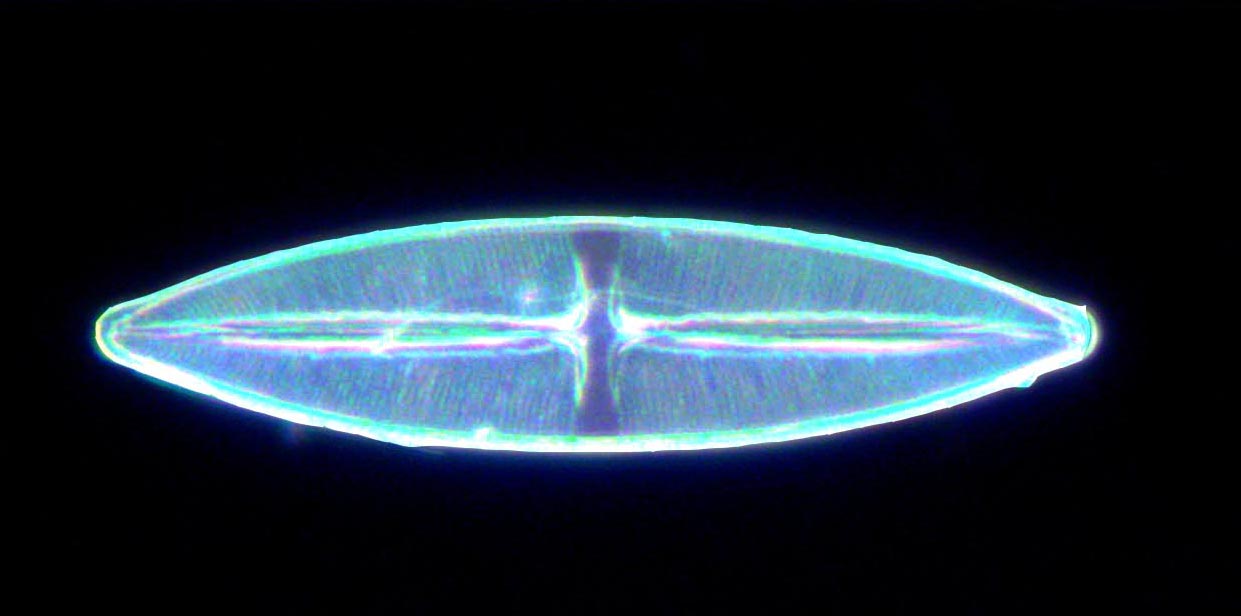

the second quarter of the nineteenth century, microscopists yearned for a greater ability to discern the fine details of objects seen under the microscope. From the time of Hooke, and Van Leeuwenhoek after him, it was noted that certain objects were more readily seen using dark ground (also known as dark field) illumination which allowed mainly oblique light from all sides to reach the specimen, and causing the background to remain mostly black while the objects being studied would stand out against the dark backtround. Objects suitable for such a type of illumination include: Unstained bacteria, yeast, and molds, dust particles, plant and animal hairs, undyed textiles, small insects, crystals, and unstained plant and bone sections. This method is not as satisfactory for visualizing periodic structures inside the subject such as diatom frustules for which uniaxial or biaxial oblique illumination is better for resolving these structures. Oblique illumination is the subject of another webpage on this site.

One variation of this is central oblique illumination

.

When the N.A. of the objective is greater than that of the condenser (or the central stop does not fully render the field black) you get COL = Central Oblique Illumination, an under appreciated technique, which, depending on the object, sometimes gives as good, or better results than Phase Contrast.

The first dedicated dark field illuminators were called

The first dedicated dark field illuminators were called Spot Lenses

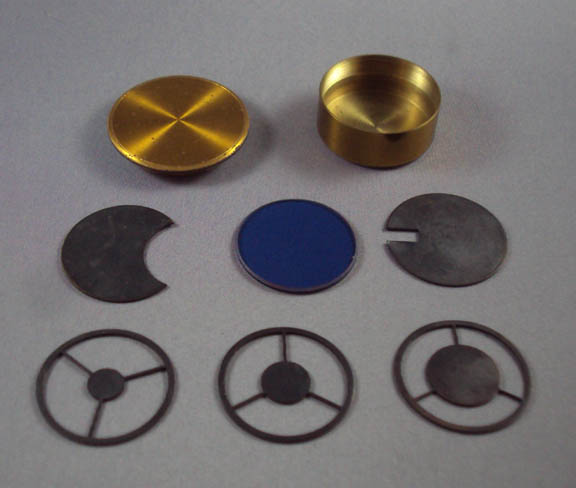

and were most suitable for use with lower powers. These are simple optical condensers with a permanent blacked-out central aperture at the top. Later removeable stops could be similarly employed inserted into a filter holder

at the bottom of condensers. These came in a variety of sizes providing a range of stop diameters for different powers. These were still not adequate for high power critical work however.

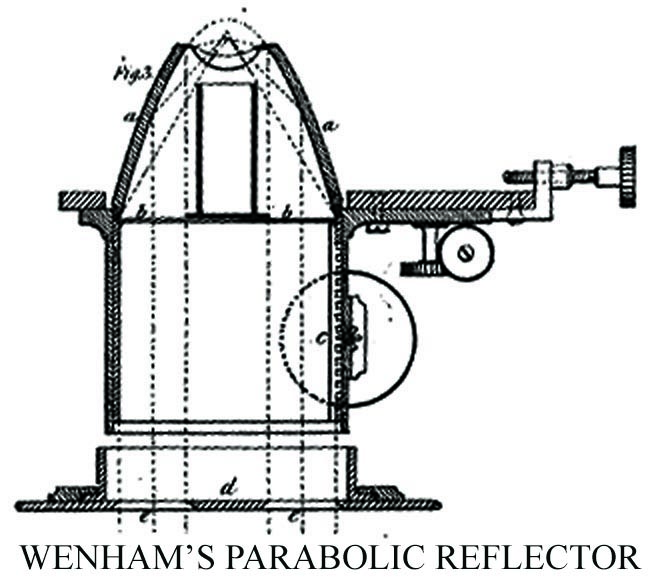

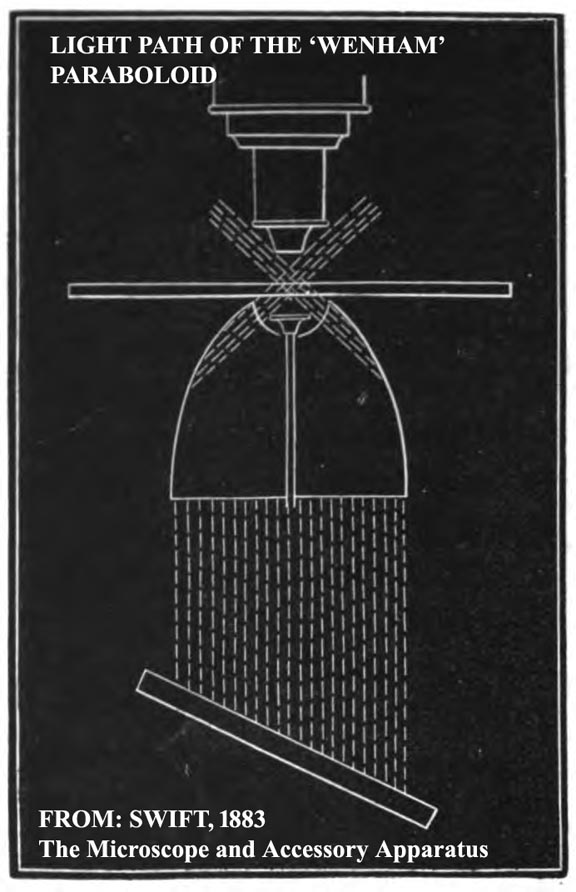

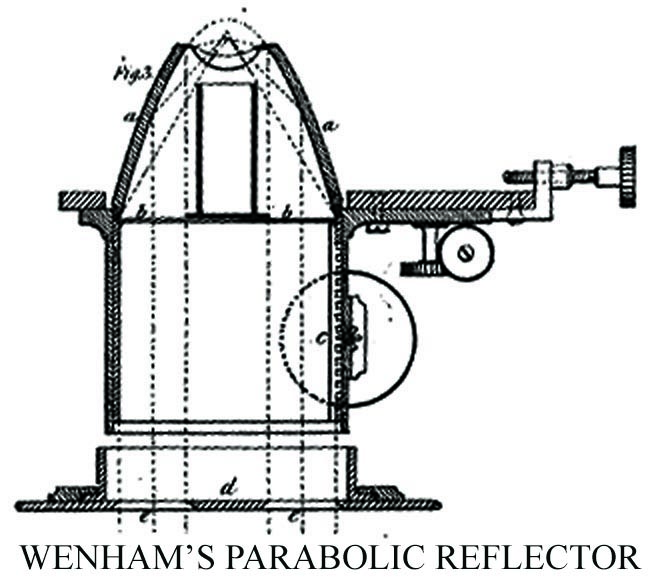

In the early 1850's Francis Wenham theorized that a better form of oblique illumination would encircle the specimen from all sides and he devised his 'Parabolic Reflector'. The parabolic reflector used an internal light path traveling off a reflector of speculum metal; the fact that this is a

mirrored surface made it intrinsically achromatic.

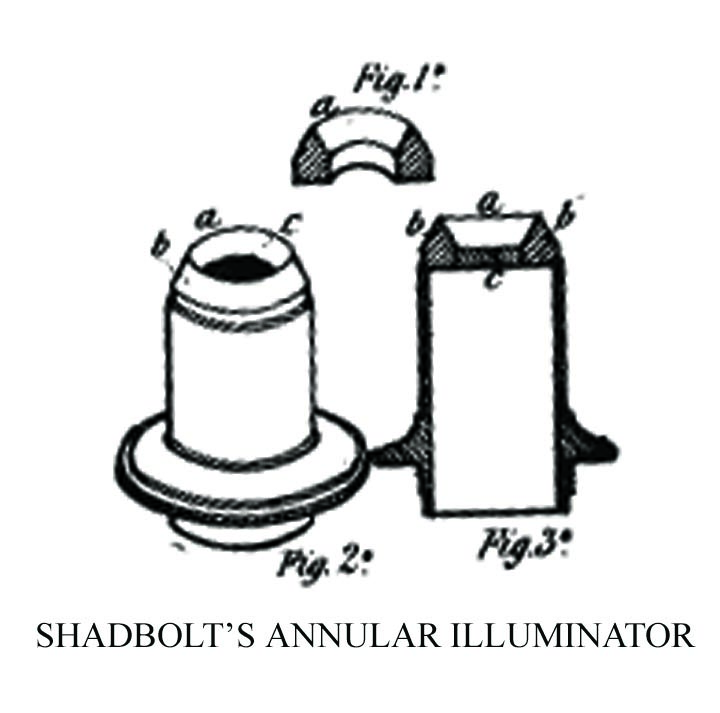

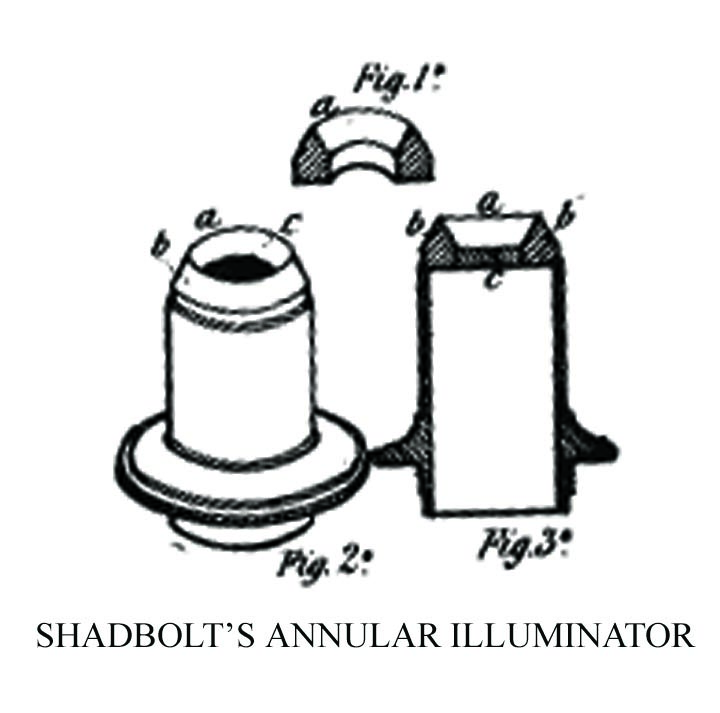

This was quickly followed by Shadbolt's 'Annular Illuminator' which used internalreflection inside a ring of glass of roughly triangular cross section surrounding an opaque central area. This type of illuminator, though very effective, and capable of concentrating more light upon the specimen, is limited to use with one focal length, hence the expensive proposition of having a different one for each objective. But Wenham's

speculum reflector would also have been expensive and difficult to make.

This was quickly followed by Shadbolt's 'Annular Illuminator' which used internalreflection inside a ring of glass of roughly triangular cross section surrounding an opaque central area. This type of illuminator, though very effective, and capable of concentrating more light upon the specimen, is limited to use with one focal length, hence the expensive proposition of having a different one for each objective. But Wenham's

speculum reflector would also have been expensive and difficult to make.

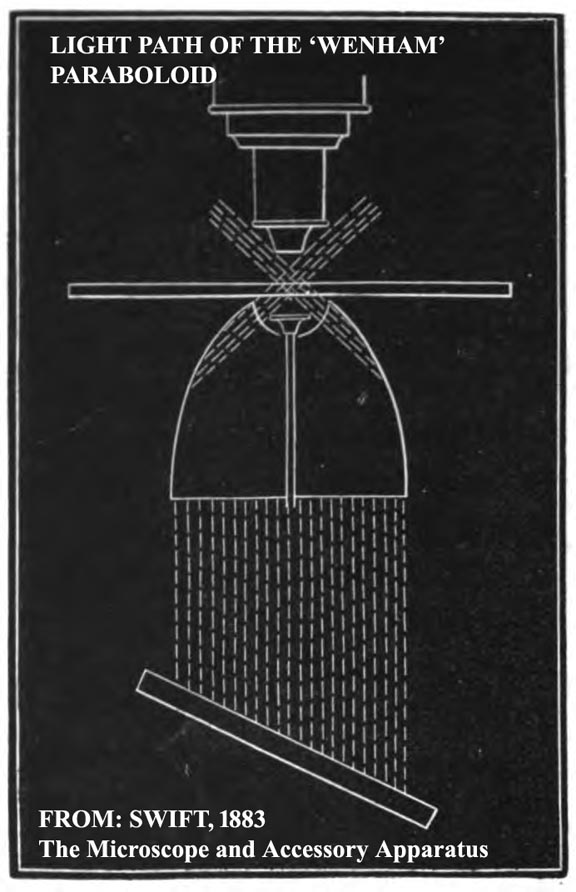

Subsequently, a hybrid device, commonly known as a 'Wenham Parabolic Illuminator,' 'Wenham Paraboloid' or

more properly the Wenham-Shadbolt illuminator, uses a parabolic glass ring surrounding an adjustable

center stop that can be moved up or down to accommodate objectives of differing apertures. The stop is moved down deeper inside the paraboloid for low power objectives, and close to the to the top for powers as high as a 1/4 inch focal length (25 X with 160 mm tube length) objective. This latter device was extremely popular and was used for many decades. It makes use of internal reflection of the parabolic glass, and is a far easier piece of equipment to make. Its

parabolic shape reduces much aberration.

Subsequently, a hybrid device, commonly known as a 'Wenham Parabolic Illuminator,' 'Wenham Paraboloid' or

more properly the Wenham-Shadbolt illuminator, uses a parabolic glass ring surrounding an adjustable

center stop that can be moved up or down to accommodate objectives of differing apertures. The stop is moved down deeper inside the paraboloid for low power objectives, and close to the to the top for powers as high as a 1/4 inch focal length (25 X with 160 mm tube length) objective. This latter device was extremely popular and was used for many decades. It makes use of internal reflection of the parabolic glass, and is a far easier piece of equipment to make. Its

parabolic shape reduces much aberration.

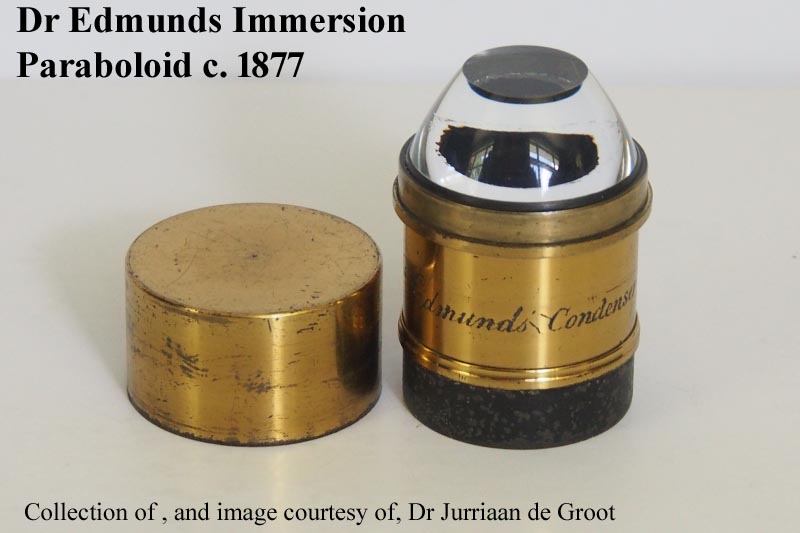

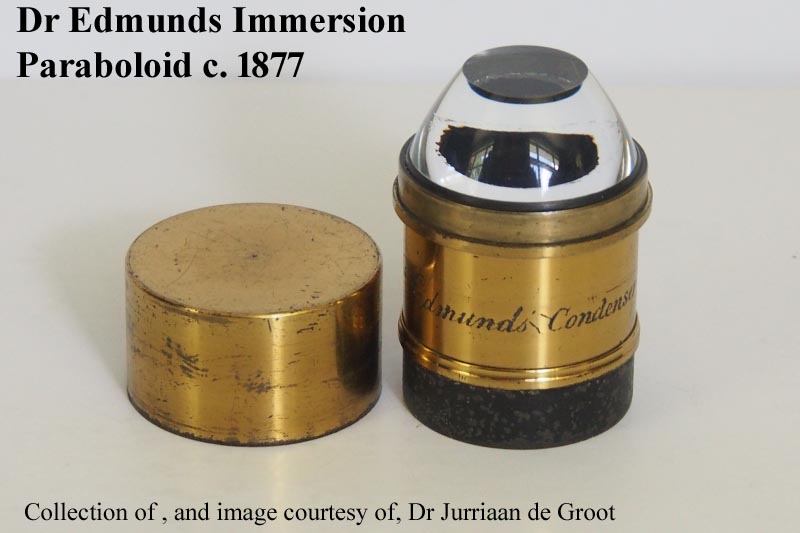

One of the earliest to design an immersion paraboloid for practical use was Dr James Edmunds in 1877.

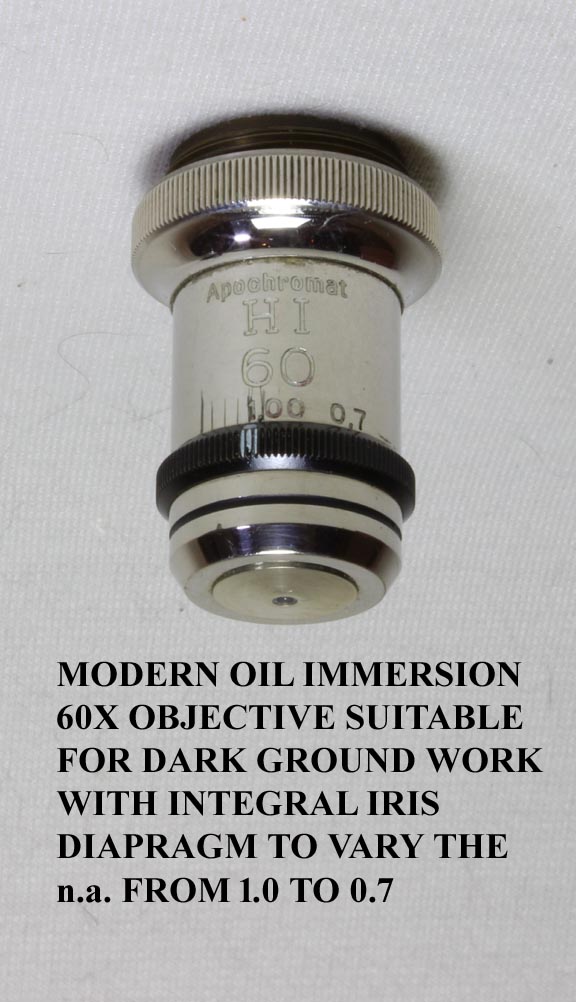

With the new knowledge came the development of better dark ground condensers for higher powers. These condensers still make use of a curved light path, usually either paraboloid or cardioid, though other forms also exist. These more modern dark ground condensers for high power all require an oil interface to the slide to function properly. The light path usually involves a paraboloid or cardioid course. These condensers are still used today.

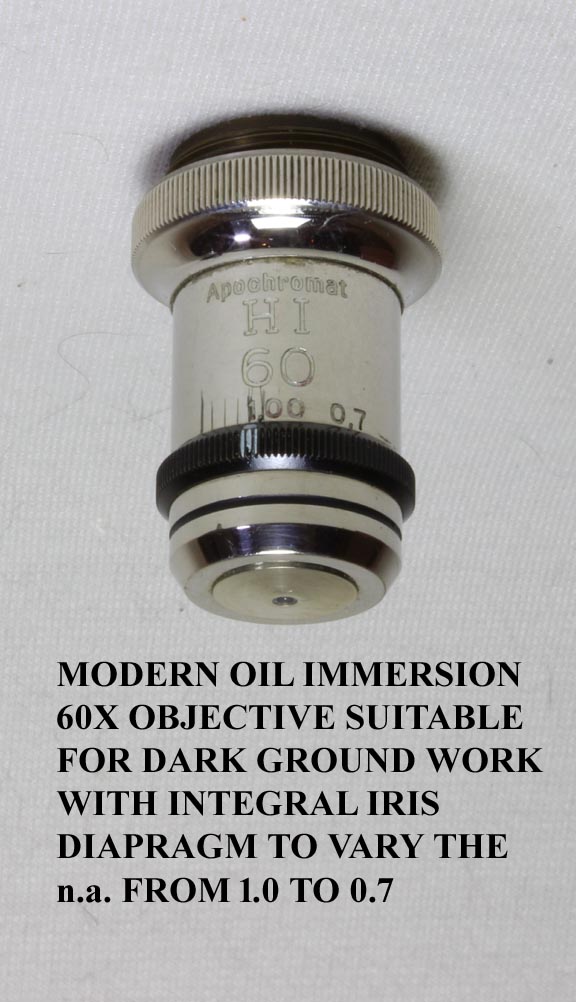

One important principal involved in high power Dark field work with these condensers, is the fact that the numerical aperture of the condenser must exceed that of the objective. To accomplish this at high power often requires reducing the numerical

aperture of the objective. This can be accomplished by the use of a 'Funnel Stop' which fits inside the objective, or in the case of high n.a. modern objectives, an iris diaphragm built-in to the oil immersion objectives. The kit by Spencer to the left illustrates the funnel stop while an example of the objective with built-in iris is shown to the right. Another example of a dark ground immersion condenser is the Watson Holos Immersion Paraboloid

.

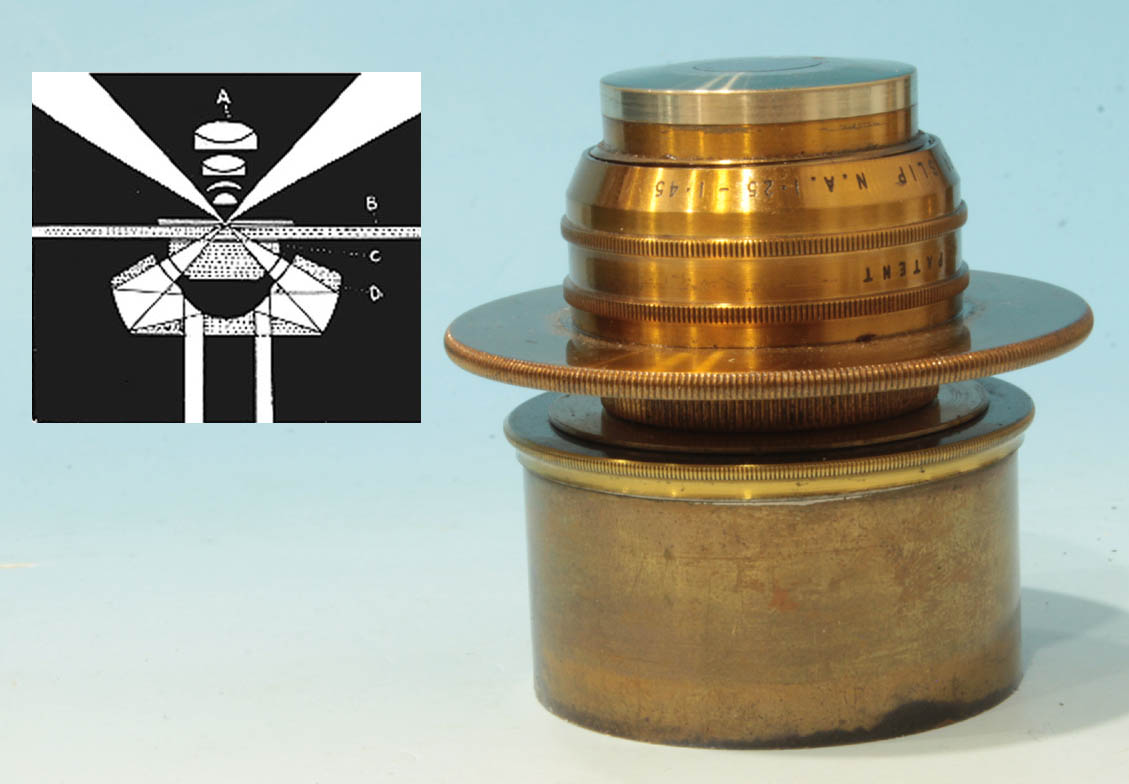

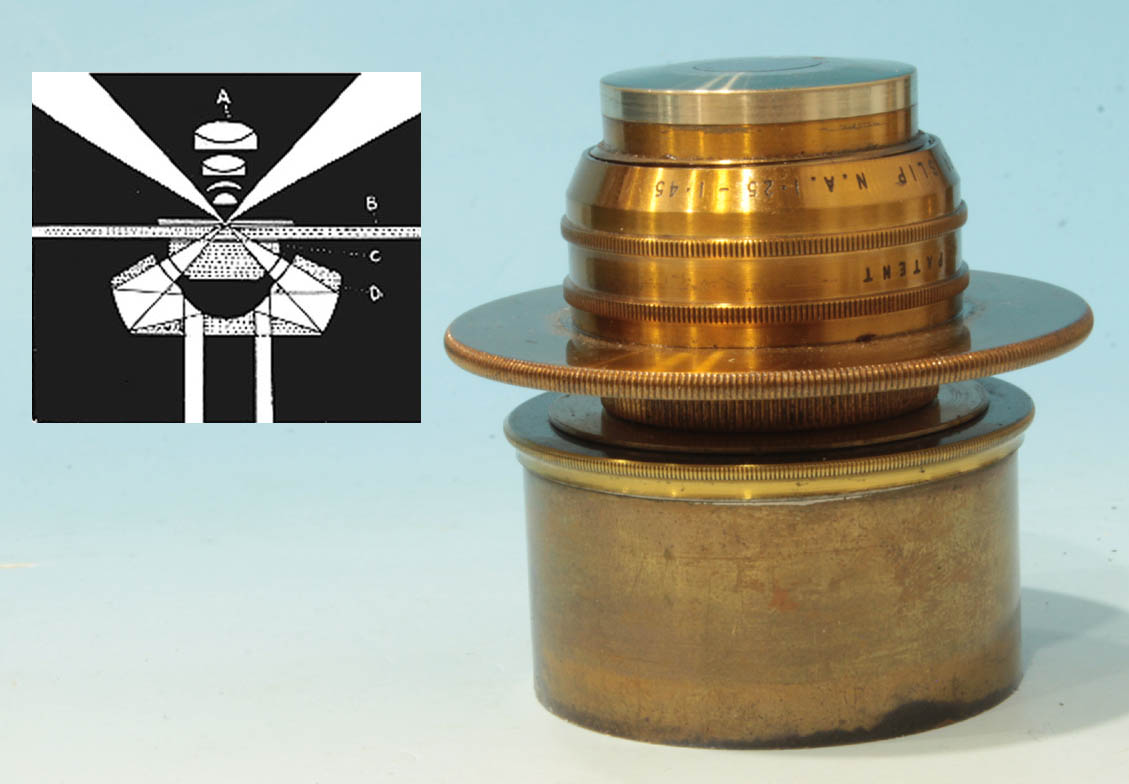

It should be noted that when immersion dark ground condensers are used, they are designed for a specific slide thickness. Nowadays slides are generally at standard thickness, but earlier this was not the case. For this reason Beck developed an immersion dark ground condenser with provision for focusing despite being immersed. This

It should be noted that when immersion dark ground condensers are used, they are designed for a specific slide thickness. Nowadays slides are generally at standard thickness, but earlier this was not the case. For this reason Beck developed an immersion dark ground condenser with provision for focusing despite being immersed. This Patent Focusing Dark Ground Illuminator

, shown to the left, was produced from about 1900 well into the 20th century.

For a detailed review of the various forms of darkground illumination now in use, the reader is referred to the superb review on the Olympus website.

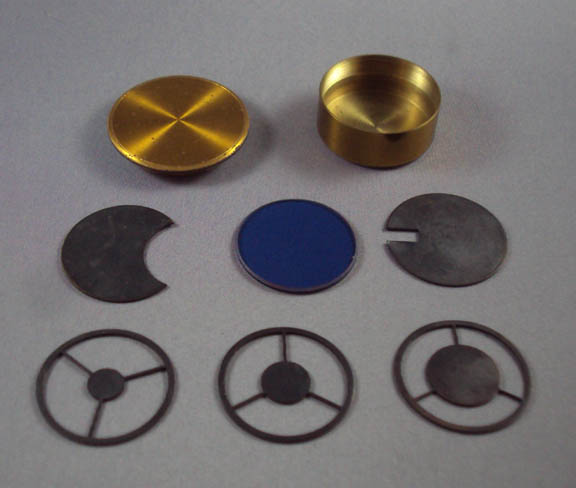

Early on, for lower power dark field work, a

Early on, for lower power dark field work, a spot lens

condenser(left) was used, but in later condensers, simple stops,

, a set of which is shown to the right, can be used which fit into the filter holder at the bottom of the condenser. This kind of fitting (stops) can be found with many microscopes in this collection that date from the late 19th to the mid-20th century. These stops are still made and sold today. The set shown to the right includes not only inserts for dark ground (the three on the bottom), but also a couple of inserts for oblique lighting. An advance over these was the Travis Expanding Stop, invented in 1906, it was the opposite of an iris which varies the aperture size, the Travis Stop varies the size of a central Stop, fitting into the filter holder of the typical Abbe and similar condensers.

It should be remembered that not only was Francis Wenham the first to suggest a paraboloid illuminator, he was also the first to suggest, (in 1856) the use of immersion fluid for optimal use of these at high power.

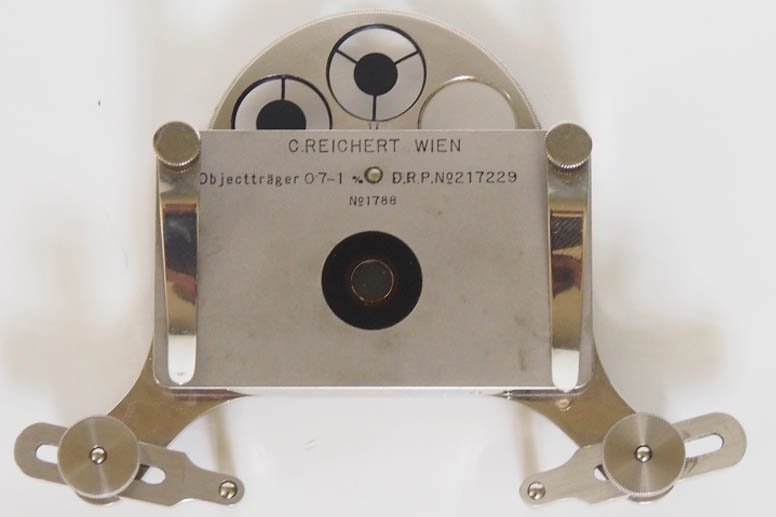

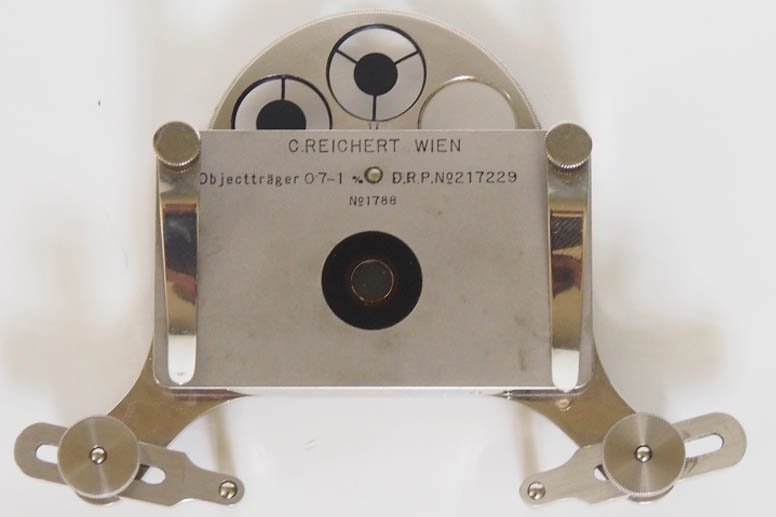

The accessory shown to the left is a Reichert dark ground condenser with a wheel of stops designed to be placed on top of the stage of microscopes without a substage fitting for a condenser. This device was shown in Reichert catalogs from the 1920s and 1930s. The pins are placed in the holes usually holding the stage clips, the condenser is centered in the optical axis and the knobs on the adjustable arms are then tightened securing it in place.

REFERENCES AND FOOTNOTES

Conrady, A.E.: 1912. Resolution with Dark Ground Illumination. JQMC 11:475-80.

Edmunds, James: 1877. On a new immersion paraboloid illuminator. JQMC V:17-21.

Quekett, John: 1848. A Practical treatise on the use of the microscope... First Ed. 178-179.

Reade, Rev J.B.: 1837. On a new method of illuminating microscopic

objects; pages 227-31 of Micrographia by Goring and Pritchard as quoted

above.

Shadbolt, George: 1851. Observations upon oblique illumination with a

description of the author's Sphaero-annular condenser. Trans Micro Soc

Lond. III: 132-133.

Siedentopf, H: 1910: Cardioid-Condenser. JRMS p 515-

Stephenson, J.W.: 1879. A catoptric immersion illuminator. JRMS

II;36-37. This design was the basis for many modern dark ground

condensers that depend upon a silvered central part.

The first dedicated dark field illuminators were called

The first dedicated dark field illuminators were called  This was quickly followed by Shadbolt's 'Annular Illuminator' which used internalreflection inside a ring of glass of roughly triangular cross section surrounding an opaque central area. This type of illuminator, though very effective, and capable of concentrating more light upon the specimen, is limited to use with one focal length, hence the expensive proposition of having a different one for each objective. But Wenham's

speculum reflector would also have been expensive and difficult to make.

This was quickly followed by Shadbolt's 'Annular Illuminator' which used internalreflection inside a ring of glass of roughly triangular cross section surrounding an opaque central area. This type of illuminator, though very effective, and capable of concentrating more light upon the specimen, is limited to use with one focal length, hence the expensive proposition of having a different one for each objective. But Wenham's

speculum reflector would also have been expensive and difficult to make.

Subsequently, a hybrid device, commonly known as a 'Wenham Parabolic Illuminator,' 'Wenham Paraboloid' or

more properly the Wenham-Shadbolt illuminator, uses a parabolic glass ring surrounding an adjustable

center stop that can be moved up or down to accommodate objectives of differing apertures. The stop is moved down deeper inside the paraboloid for low power objectives, and close to the to the top for powers as high as a 1/4 inch focal length (25 X with 160 mm tube length) objective. This latter device was extremely popular and was used for many decades. It makes use of internal reflection of the parabolic glass, and is a far easier piece of equipment to make. Its

parabolic shape reduces much aberration.

Subsequently, a hybrid device, commonly known as a 'Wenham Parabolic Illuminator,' 'Wenham Paraboloid' or

more properly the Wenham-Shadbolt illuminator, uses a parabolic glass ring surrounding an adjustable

center stop that can be moved up or down to accommodate objectives of differing apertures. The stop is moved down deeper inside the paraboloid for low power objectives, and close to the to the top for powers as high as a 1/4 inch focal length (25 X with 160 mm tube length) objective. This latter device was extremely popular and was used for many decades. It makes use of internal reflection of the parabolic glass, and is a far easier piece of equipment to make. Its

parabolic shape reduces much aberration.

It should be noted that when immersion dark ground condensers are used, they are designed for a specific slide thickness. Nowadays slides are generally at standard thickness, but earlier this was not the case. For this reason Beck developed an immersion dark ground condenser with provision for focusing despite being immersed. This

It should be noted that when immersion dark ground condensers are used, they are designed for a specific slide thickness. Nowadays slides are generally at standard thickness, but earlier this was not the case. For this reason Beck developed an immersion dark ground condenser with provision for focusing despite being immersed. This

Early on, for lower power dark field work, a

Early on, for lower power dark field work, a